Britt van Duijvenvoorde, PhD Researcher, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam //

I can hardly imagine how Helena felt when she heard that “the signatories put more credence in the words […] of a council [raad] than of the girl Helena and her testimony”—though I suspect she saw it as a profound injustice.1 These words were ushered against Helena, who was entwined in a lawsuit about her enslavement with the Dutch colonial government at Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) in 1790. I dedicate this first blog of our Voices blog series to Helena, whose story exemplifies how the words of enslaved individuals were discredited by colonial officials. Yet at the same time, it stands as a testament to the irrepressibility of their sounding.

Helena lived in the city of Colombo, on the island of Ceylon. At that time, Ceylon was a Dutch colony. The territory over which the Dutch East India Company (VOC) claimed sovereignty covered nearly the entire island, except, to some extent, the inland kingdom of Kandy. This sovereignty claim, importantly, involved the enforcement of law. Still, Dutch colonial justice system at Ceylon was inherently multicultural in nature; it included local and indigenous legal traditions, such as in the adaptation of the local Tamil laws of Malabarian people, called the Thesewalanai. One important element of Dutch colonial law was the regulation of enslaveability—or, who could be enslaved, through which means, and under what conditions? By regulating enslaveability, the VOC justice system attempted to control people’s free and slave status. Yet, the regulation of enslaveability through law at times also enabled enslaved individuals to make use of colonial law to their own benefit. And this is where Helena enters the story.

In 1790, Helena filed a petition to the secretary of police regarding her enslaveability. After her supposed owner, Matthijs Gomes, had died, Helena found out that the estate masters of Ceylon had requested the issuing of her slave letter—a so-called ola, or a written proof of one’s slave status. As proofs of enslavement, slave letters were crucial in controlling enslaved individuals. Without a slave letter, ownership of the respective individual was deemed illegal from VOC perspective. Sometimes when a slave letter had disappeared, the Court could allow new slave letters to be issued. Yet, for this, the Court needed to be certain – and thus, investigate – whether the individual was, according to VOC legal standards, enslaved. This also happened in Helena’s case.

In her petition, Helena did two things. Firstly, she filed a petition stating the reasons why she was “a free woman” and, secondly, she presented witnesses who testified this on her behalf. Helena stated that she and her mother Susanna had indeed worked for Matthijs Gomes “for a living and clothing, as they were very poor people”.2 The Court’s testimony also discussed Helena’s mother and grandmother, but for another reason. Dutch-Roman law held that slave status was inherited from mother to child. References to the fact that Helena was born “in the obedience [gehoorzaamheid] and out of the woman [meijd] Susanna who belonged as possession to chitti [merchant caste] Matthijas Gomes” were meant, clearly, to tie her down through her ancestry.3 From the Council’s summary, we furthermore learn that Helena had a daughter. We may very well wonder if this was this not only Helena’s fight for freedom but also on the behalf of her daughter, whose freedom depended on Helena’s.

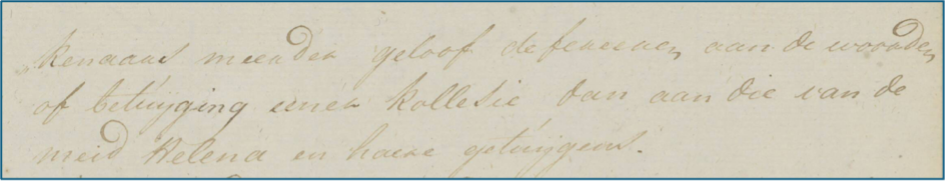

Helena was facing an army of colonial documents and witnesses brought forward by the estate masters to prove her enslaveability. During this first trial, the Court claimed to have “complete belief” in the truth of the provided documents and asserted that “the signatories put more credence in the words or testimony of a council than of the girl Helena and her testimony.” With her credibility diminished at the outset and little opportunity to make her case, the Court declared Helena to be a slave.

Nevertheless, it did not end here. Helena continued the legal fight for her freedom through an appeal. And this time, she found an unexpected ally in the legal officials that took over the case. These officials deemed the previous ruling unfair and overturned the verdict; after all, Helena’s slave status had been illegally settled “without interrogating the girl Helena or giving her the opportunity to explain herself in relation to the testimony of her opponent”.4

Though Helena’s case continued, I have not been able to retrace her steps any further. I cannot retell her interrogation, but what I can say is the following. Stories like Helena’s are important because they show us a lot about how credibility is constructed. Which stories were deemed believable in colonial contexts is often shaped through the powers of documents and bureaucracy, and focusses on a specific group of European, upper-class men. Helena shows that these stories could be and were, in fact, often contested and therefore less powerful than they seemed.

Helena’s story does not end here. She leaves us with ethical questions regarding archival and historical study such as How do we give credence to stories discredited in the very documents that narrate them? By what means did enslaved individuals undermine the stories told about them? And which stories did they tell in return?

- NA, 1.04.02, 3893, 549. ↩︎

- NA, 1.04.02, 3893, 548: “voor hunne kost en kleederen, wijl zij zeer arme lieden geweest zijn.” ↩︎

- NA, 1.04.02, 3893, 547: “dat meerm: Helena onder de gehoorzaamheid en uit de den Chittij Matthijs Gomes in eijgendom toebehoorende meid Susanna gebooren is.” ↩︎

- NA, 1.04.02, 3893, 550: “zonder de meijd Helena gehoord of aan haer gelegentheid gegeven te hebben om zig over de getuijgens van haere parthij te kunnen verklaeren.” ↩︎