Martijn Veenhuijsen, MA History at Radboud University //

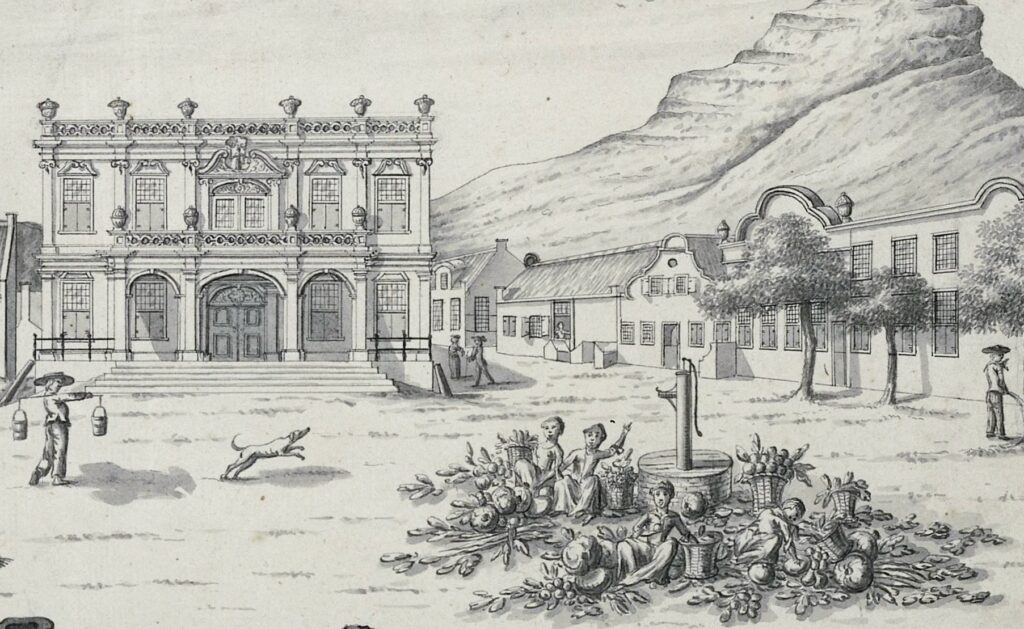

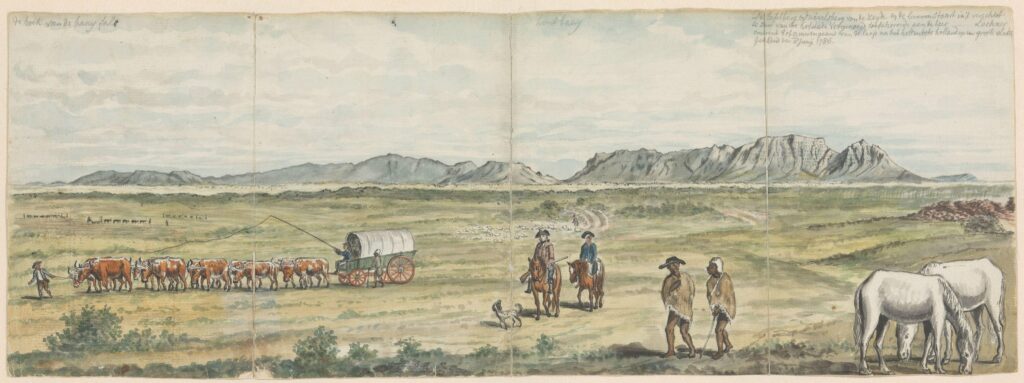

Strategically located halfway between Europe and Asia, between 1652 and 1795, the Cape of Good Hope functioned both a refreshment station and settler colony within the global network of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). During this period, over 60,000 people were enslaved and brought to the colony, originating from places such as Madagascar, Mozambique, India, and the Indonesian archipelago.

Many of these enslaved people were women. They lived and worked in households, on farms, in workshops, and on the busy harbour wharfs of Cape Town. Yet when we turn to the archives, their presence often slips through our fingers. These women are rarely described in detail and are almost never recognised as workers in their own right. The records that survive from the colonial period — tax registers, censuses, legal documents, and private correspondence — were written from the perspective of colonial authorities and slave owners. Enslaved women’s labour, essential for colonial society, was barely acknowledged and therefore not archived. This silence raises a deceptively simple question: What forms of labour did enslaved women perform within the slavery system of the Cape of Good Hope, both inside colonial households and outside?

The challenge of the archive

In my Master’s thesis, “Slavernij in de Nederlandse Kaapkolonie: De onzichtbare arbeid en rol van slaafgemaakte vrouwen in het tussenstation Kaap de Goede Hoop (1652–1795),” I have looked at the judicial records of the Council of Justice at the Cape to find out more about enslaved women’s work. Due to their voluminosity, these judicial records harbour great potential of shedding light on enslaved women’s workers’ positions. Yet, detailed in information these records may be, these documents never designed to expose labour, Instead, enslaved women appear only when their lives intersected with colonial law: as accused, testifiers or persecuted.

If one searches the records for nouns — for occupational titles like maid, washerwoman, or vineyard worker — there are little to none results. Enslaved women were not allocated any such official labour roles. A verb-oriented method however helps expose the work performed by enslaved women in practice. The idea is simple yet powerful: instead of searching for nouns (roles, titles, categories), one searches for verbs — the actions that reveal what people actually did. In this sense, each verb acts like a lens, bringing into focus a moment of labour that the archive did not set out to preserve.

Take Flora van de Caab for instance. She appears as a witness in a legal case where she testified that she had to slaughter (slachten) a goat, zouten (salt) the meat, and prepare the cuts for her owner’s household through cooking.

In vineyard cases, women appear not under the title of “vineyard worker,” but through their actions: druyven treden (treading grapes), dragen (carrying), snoeien (pruning vines). For example, in a case against Thunnis van Aart, the enslaved Sara gave a statement to the Council of Justice in which she stated that she was picking and cutting grapes while also tending the sheep when Theunis stole some.

What we see in the examples above is that enslaved women’s labour surfaces in phrases like een geit slachten (to slaughter a goat), wasschen (to wash), druyven treden (to tread grapes), or hout halen (to fetch wood). These verbs reveal skilled culinary labour, knowledge of preservation, and the centrality of women in food production. This was not incidental “help” but specialised work on which households depended. Vineyard cases testify that women were active participants in the Cape’s lucrative export industries: the wine economy. Such verbs were rarely part of the core issue of a legal case. They appear incidentally, as part of testimonies or side remarks. But each verb is a fragment of labour; a clue to the tasks that structured women’s daily lives.

By systematically identifying and cataloguing these verbs across 200+ court cases, I was able to reconstruct the activities of more than 300 enslaved women. For a verb-oriented method to pick up on gendered labour, I employed a gender-sensitive analysis. By comparing the verbs attached to women with those describing men’s work, it became clear how gender shaped labour. This comparison helped highlight the specifically gendered dimensions of slavery at the Cape. Women were often associated with domestic and bodily care, but they also appeared in agriculture, viticulture, and skilled food preparation. Men’s work, in contrast, was more often recorded in terms of heavy labour or craftsmanship. In addition, by constructing a dataset of relevant verbs, I was able to create a structured overview of enslaved women’s work. Doing so made it possible to move from individual anecdotes to broader patterns. This dataset brought to light the recurrence of certain tasks, the overlaps between domestic and agricultural labour, and the structural importance of women’s contributions across the colony. It revealed women’s work over a much more varied spectrum—across kitchens, vineyards, washhouses, farms, and fields—than the stereotype of “domestic slavery” would suggest.

Towards a working history The verb-oriented method does completely combat the fact that the voices and activities of enslaved women are still filtered through the language and authority of colonial scribes. But the method does allow us to shift perspective: to see enslaved women as workers, defined not by labels but by their actions. The result of my master’s thesis is a dataset over 300 enslaved women extracted from VOC judicial records. This dataset is recently published on the Dataverse of the International Institute of Social History (IISH), where it will be openly accessible for further research:

To view the dataset, visit the Dataverse