Camille Le Brettevillois, PhD Researcher, International Institute of Social History //

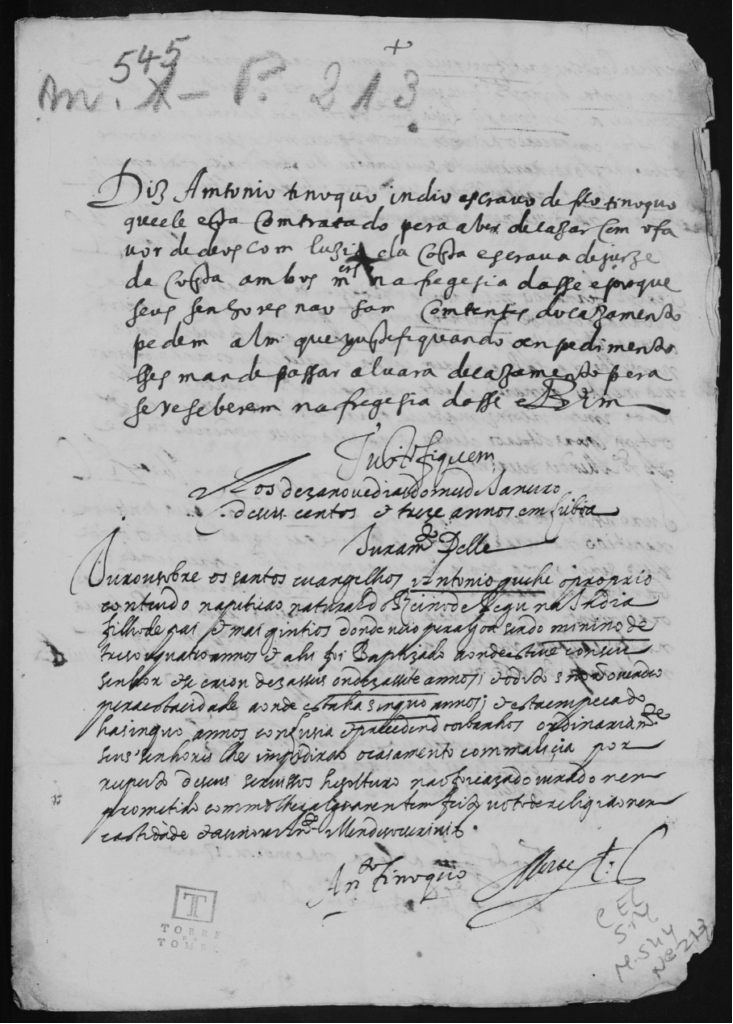

In 1613, in Lisbon, António Tinoquo, an enslaved man originally from the Bay of Bengal, appeared to the ecclesiastical trial of Lisbon to get married with Luzia da Costa, an enslaved women originally from Angola. The precious and unusual precision of António’s statement in court allowed me to write this blog post.

Maybe he was lucky to have such a good memory. Maybe he had to work hard to try to remember. Maybe he invented the whole story and asked his circle to follow him into this declaration. In any case, António Tinoquo, 21 or 22 years old, had to tell a part of his life to the ecclesiastical court. The situation might seem already delicate: wanting to get married while being a slave (escravo) is not the best possible situation for a couple in Lisbon, 1613. Even if marriage was a sacrament (thus, a right accorded even to the enslaved ones), it was not a foregone conclusion. You had to put yourself in a good light to the Church, especially when you knew, like António and his bride Luzia, that your master would not approve such a union. You had to prove that you were a good Christian, who deserved to go through the sacrament of marriage.

António’s partner, Luzia, was less suspicious in the eyes of the archbishop of Lisbon: captured in Angola when she was a child (moça), she was sent and sold in Lisbon at an early stage of her life. Maybe she never left the city, which made her Christian life and behaviour easier to track for the religious officers. The case of António however seemed to have called on the authorities to be more cautious.

According to his oath and declaration, he was born around 1591-1592 in the Kingdom of Pegu (Reino do Pegu). This could refer to a location situated in the Bago region, in today’s Myanmar, although it is hard to know what António and/or the officers meant by this appellation. Were they referring to the city of Pegu? To the whole region? In any cases it is more likely that António was originally from the east-part of the Bay of Bengal, somewhere in the Burma region, where he has been captured and deported to Goa in 1594-1595. He was 3 or 4 years old then.

In 1595, the city of Pegu has been besieged by the Ayutthaya armies. This siege occurred during the Burmese Siamese War (1593-1600), where some Portuguese mercenaries were hired in the Ayutthaya military forces and took the advantage of the local conflicts to erect a Portuguese settlement in Pegu.

Was António a war captive child, sold and enslaved during this conflict? This hypothesis sounds plausible, and might have been the fate of many children, women and men. After being captured, António was sent to Goa, where he was sold and spent more than ten years of his life. Since Goa was a Portuguese settlement, the religious officers who interrogated António felt the need to make sure his life in the “Rome of the Orient” was indeed the life of a good Christian. This was not special treatment however: the Church had to make sure the young man was not married there, or that his past wife was indeed dead in the other case. Otherwise, the act of bigamy could have been considered as serious sacrilege.

Luckily for António, two men, Sylvestre de Meneses and João Ferreira, testified in his favour in front of the ecclesiastical court of Lisbon. Both were summoned by the officers of the archbishop. They appeared four days after António’s declaration. Like him, they were identified as “Indians” (indio). Unlike him, an escravo, they both had the status of manumitted slaves (forro). They were approximately 10 years older than him. Both of them knew António for 15 or 16 years. They arrived in Lisbon together on the same ship, around 1608. Sylvestre and João were the perfect witnesses to testify António was not married in Goa: the three men knew each other since the childhood. They apparently kept in contact once they arrived in Lisbon, where they managed to have their own lives, although not in the same parishes.

Did António expect the officers of the archbishop to require proofs of his good behavior in Goa? Did Sylvestre and João really know António? Or did he talk to them to make sure their declaration would fit his? In all these possibilities, the fact remains that these two people helped this young man to assert his right to get married.

The summary of this trial is closed by their testimonies and the judge’s decision to grant exemption from the publication of banns of marriage, to allow the spouses to get married without their masters knowing. António and Luzia were not an exception. In Lisbon, hundreds of enslaved people appeared in the ecclesiastical court to attempt to get married despite their master’s disapproval. Their declarations and the testimonies of witnesses were then decisive to get access to this right. The case of António highlights the need and the existence of a solidarity network among enslaved and manumitted people in the city.