Pascal Konings, PhD Researcher and ESTA Project Coordinator, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam //

On Wednesday, October 1, 2025, the Joint Projects on Slavery (IISH-Radboud University) organized the hybrid seminar “Dependency, Bondage and Slavery in Northern Eurasia” at Radboud University, as part of their monthly seminar series. This series focuses on the global turn in slavery studies that urges us to bring together the study of histories of slavery from across the globe, from Asia to the Atlantic, from local regimes of slavery to the impact of colonial slave trade and slavery.

As with previous seminars in this series, the October seminar yielded fruitful discussions, perhaps even more so than usual. And so, to bring the esteemed reader of this blog up to speed, I will briefly introduce two presenters who shed light on dependency in early modern Northern Eurasia. First, we were delighted to welcome Angelina Kalashnikova,postdoctoral researcher and KiTE fellow at Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel. Her work focuses primarily on the history of Muscovy from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century and displays expertise in source studies, diplomatics, and paleography. Kalashnikova examines topics such as judicial procedure, the incorporation of Siberia into Muscovy, processes of (de)colonization, interethnic marriages, and slavery. Secondly, we welcomed Aleksandra Modelina, SA at the Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies, and master’s student at Bonn University. She studies medieval history and is currently writing her thesis on historiography and the representation of space. Her broader research interests include imagined geographies and mapping in high medieval Western Europe, the history of the VOC, and Russian serfdom in the early modern period. Since July 2024, Modelina has been doing a wonderful job working at the BCDSS as a student assistant for the benefit of the Exploring Slave Trade in Asia (ESTA) database project.

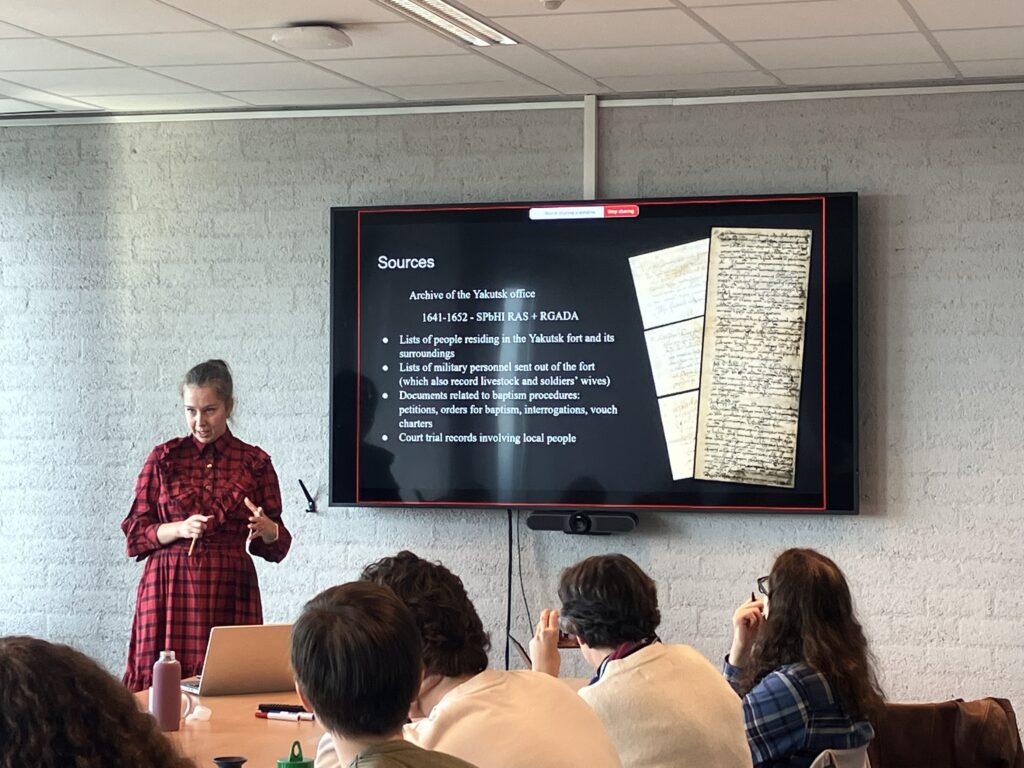

In the first presentation, Angelina Kalashnikova explored the incorporation of Siberia into the Russian Empire and the intertwinement of state and local practices in forming coercion, dependency and cross-cultural relations. By sharing in detail source material, especially focusing on its challenges, limitations and biases, she highlighted the role of indigenous people and the subjugated position of women in general in different bondage regimes or human trafficking practices that clashed or connected in early modern Siberia. Kalashnikova stressed the importance of critically engaging with documents like petitions, sale deeds, and baptism records because of its seventeenth-century formulaic style that effectively silenced many voices trapped in these bureaucratic Russian documents. After all, these sources were mostly written from an imperial perspective – Kalashnikova briefly touched upon the historiographical debate whether we can call this colonial or not – and thus personal life stories were not of concern to the target audience, i.e., state officials. She reiterated the point that women in these sources were consistently depicted as objects – of commercial transactions, for example, or of conversion.

Aleksandra Modelina’s presentation focused on the history of bondage and serfdom in early modern Muscovy, particularly on specific forms of bondage found in the social categories of serfs (peasants attached to the land) and holops (bonded servants). Especially the latter category proved intriguing to many global historians at the seminar, seeing that the status of holops could be obtained through a myriad of means, including war capture, being born into servitude, self-sale and debt. After all, these practices were present all over early modern Asia as well, even though local contexts might have differed greatly. Modelina, too, discussed source material that testify of these structures of dependency and the people caught up in it. Take for example the kabalniye knigi (bondage registers). The latter recorded sale and self-sale, terms of service or subjugation, the duration of the dependency and the conditions for manumission, or the prikaz or Orthodox Church registers that recorded births, marriages and deaths, but also sale deeds, permissions for (re)marriage of holops and serfs and their disappearance from the community in case of flight. Presenting some of the translated sources, Modelina also pointed out their formulaic structure and bureaucratic purpose that omitted individuals’ motives for entering bondage, though she stressed the value of the descriptions of servants that landlords included in these deeds (‘I am of medium height, with red hair, and grey-red eyes’) and its possibilities for further research.

During the plenary discussion, the group and the presenters debated the differences and similarities of the situations in Siberia, Muscovy and – more broadly and globally – Asia. This is, of course, closely tied in with the question whether – and if so, to what extent – we should consider various constellations of bonded servitude in early modern Northern Eurasia forms of slavery. It is beyond doubt that examples from these inspiring presentations will be taken into account when the Joint Projects on Slavery will return to its internal series of conceptual discussions (‘what is slavery?’). The presenters also discussed with their audience the challenge to extract subjugated voices from the source material, which was echoed by many in the group. All in all, the seminar proved to be highly relevant for anyone working with coerced labor regimes and food for thought for global historians of slavery in particular.

The Joint Projects’ next seminar is set for Tuesday 2 December 2025, 15:00 CET at the International Institute for Social History in Amsterdam, when postdoctoral researcher Miguel Rodrigues (IISH) will give his (hybrid) presentation “Spiritual Salvation, Enslavement, and Creolization: The Formation of Colonial Societies in the West African Archipelagos of Cape Verde and São Tomé (16th–17th Centuries)”. I believe I speak for the entire group when I say that we are very much looking forward to this presentation!

Many thanks to Sanne Muurling, Britt van Duijvenvoorde and Hélder Carvalhal.