August 13, 2025

Bethany Warner, Junior Researcher, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

On 14th to 18th July, the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organisations (ADHO) hosted its annual Digital Humanities conference at NOVA, Lisbon.

The conference, with the theme of “Building Access and Accessibility, Open Science to all Citizens” explored a wide range of digital humanities themes, methodologies, and disciplines. Across 2 workshop days and 3 days of conference, researchers presented a huge diversity of topics and methodologies to approach humanities subject, from LLM integration in research workflows to image analysis in historical newspapers and more, conducted in a way which furthers the conference aims of furthering access, open science, and accessibility.

As part of the Voices project group, my work consists in creating handwritten text recognition (HTR) for colonial sources and slavery studies. This involves creating HTR models which make it possible to automatically transcribe historical documents—significantly advancing new avenues of historical research. At the conference, I had the opportunity to present our progress using Loghi, an open-source HTR tool developed at the KNAW. So far, we have successfully transcribed over half a million pages of colonial archival material, including from the Dutch East-India Company (VOC) archives. In addition, we have developed an HTR model for early modern Portuguese, with models for other languages currently underway. The resulting HTR makes the material searchable for the first time ever and opens the door for different kinds of computational and non-computational historical research.

HTR is a complex computational task due to language differences and the huge array of handwriting styles across time and space. This challenge has been taken up and explored by researchers across the world as machine learning models are rapidly improving. At the conference, I had the opportunity to engage with other presenters working on solutions to complex computational tasks such as abbreviations, multidirectional text and detecting authors by minute character differences. Many of these methods and tools being developed in an open-source manner, contributing both separately and collectively to efforts to make archival material more accessible. By using open-source tools, and by ultimately publishing our models, we hope to similarly contribute to this call.

July 23, 2025

Britt van Duijvenvoorde, PhD Researcher, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam

Pascal Konings, PhD Researcher and ESTA Project Coordinator, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam

Upon Cornelis Chastelein’s death in 1714, the 200 individuals who had lived their lives in slavery on the pepper plantation of Depok (West Java) begot their freedom, as well as collective control over the land. This exceptional and relatively unknown story of humanism, slavery, and landownership was the topic of the seminar Depok: A Story of (Im)material Heritage of Slavery, which took place at the IISH on the 22nd of July 2025. Four enthusiastic speakers explored different aspects of this history, each drawing on their expertise. Jan-Karel Kwisthout, himself a descendant of one of the freed enslaved families, presented a comprehensive historical narrative of the town of Depok, located about 35 kilometres south of Jakarta. He introduced us to the figure of Chastelein whose humanist vision formed a set of Christian social rules that the now-free individuals in Depok were to adhere to for them to be allegeable for a claim to the land. Kwisthout elaborated on the place of origins of the enslaved people, such as Bali, Bengal, Makassar, Surabaya, and the Coromandel Coast, and the opposition they faced from the Dutch East India Company (VOC) that was unsurprisingly unsympathetic towards their land claims. But he also propelled this history into the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries by sketching the life trajectories of the Depok Lama community through the imperialistic times characterized by missionary activity and World War II, to today’s urbanization.

Thereafter, Sherlien Sanches and Lukas Eleuwarin from the Dutch Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage (KIEN) focused on the heritage of Depok in contemporary times by presenting their project – a joint effort with Dutch Heritage Agency (RCE) – on intangible heritage of Depok Kota (the wider, recenty developed city) and Depok Lama (Chastelein’s plantation plots). They shared with us stories of collaboration with local students and inhabitants, and the oral histories that still circulate within the communities living in Depok. Wrapping up the event, we were honoured to have Prof. Dr. Bambang Purwanto (Gadjah Mada University, Yogjakarta) reflect on the presentations and the significance of Depok in a larger story of slavery in the Atlantic and the Indonesian Archipelago. The story of Depok, he insisted, is not just obscured in a story of Transatlantic slavery nor in Dutch memory; it is vital for the Indonesian history of slavery to incorporate the exceptional story of Depok as well.

All in all, the importance of storytelling is one of the main take-aways of the event. Storytelling is one of our best chances to make silenced histories be heard again, whether they pertain to the unfolding of a history anchored in personal or collaborative communal heritage and memory-making, or nationalistic or academic discourses. We sincerely hope that this event has contributed to this storytelling by providing a platform for the oral history of Depok to be told, shared, and amplified.

July 8, 2025

Philipp Huber, PhD Researcher, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam

On 30 December 1607, the Lisbon Inquisition questioned Vitória Dias. It had already questioned many others about her. Vitória was part of the merchant Henrique Dias de Milão’s household. This household consisted of “New Christians”, former Jews converted to Christianity but often suspected of secretly remaining Jews. The inquisition’s suspicions were first raised after members of the household had tried to board a ship bound for Northern Europe. Now, they questioned the members of the household, hoping that they would testify against each other. Their goal was to find people who, even after having publicly converted to Christianity continued to practice Judaism in secret.

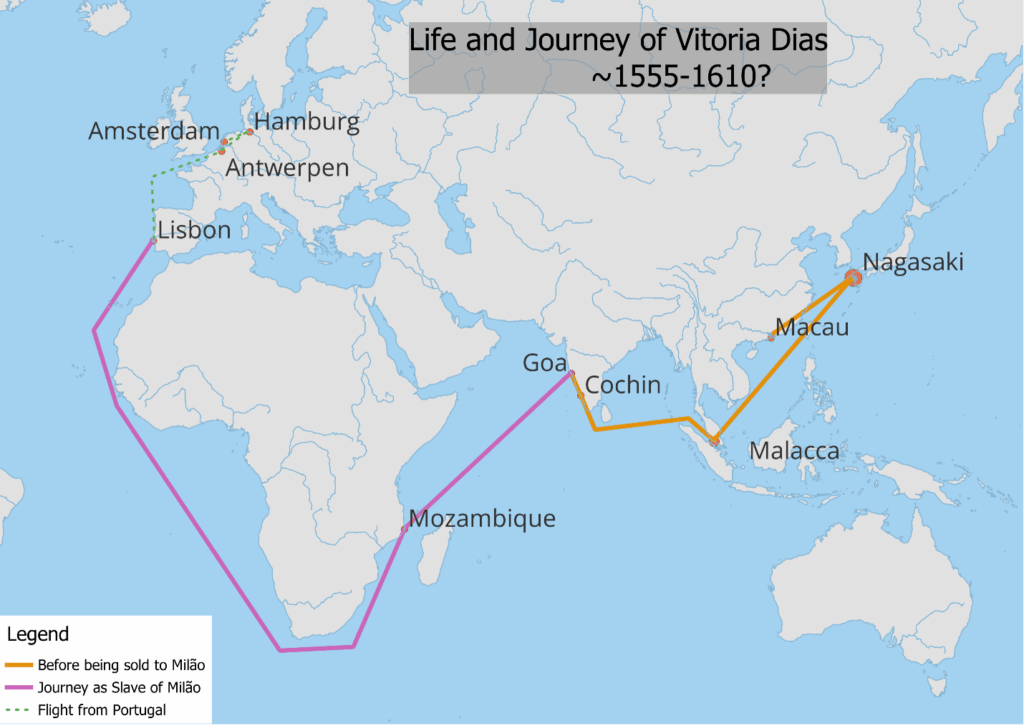

At the beginning of her interrogation, Vitória was asked to provide a brief life history. Her statement reveals that she was different from the other members of this large household in one key respect. While most were relatives of Henrique, Vitória had become part of the household as an enslaved woman, owned by him. Although she had been freed a few years prior, the inquisition still referred to her as a slave. She was not originally from Lisbon, indeed she did not know where she had been born. Vitória estimated her age at above 50, meaning that she was likely born around 1555. She said that she was from China, but did not know in which “realm”(reino) or city she was born. She had been so young at the time of her enslavement, that she did not even remember her parents’ names. Importantly, especially from her interrogators’ religious point of view, Vitória remembered that she had received a Christian baptism on a ship close to Japan. She was later taken to Cochin (Kochi) in India where she was sold to a woman named de Meneses. From Cochin she was taken to Goa, the capital of the Portuguese Empire in Asia, where she was sold to de Milão. She also claimed to have received her Confirmation from the bishop of Goa. When de Milão returned to Lisbon, he took Vitória with him. She had been living with him ever since.

After the inquisitors had written down Vitória’s statement, she was returned to her cell. She stayed there and was questioned thrice more, until on 8 May 1608 she finally confessed to knowing of the presence of Jews in the de Milão household. Later she also revealed that she had been converted to Judaism by Guiomar Gomes, Henrique’s wife, and that she had participated in Jewish rituals together with the others. Vitória was sentenced to re-education as a good Christian in a religious school.

In 1610, Vitória was again in front of the inquisitors She had again tried to flee the country together with Isabel Henriques, the daughter of Guiomar Gomes. For the inquisitors, the most important facts of this interrogation were likely, again, Vitória’s insistence that she had been baptised and, moreover, that she had received Confirmation and knew the most important Catholic prayers (Lord’s Prayer, Ave Maria) as well as the fact that she had received communion while in Lisbon.

To our modern eyes, her travels appear more noteworthy. They reveal that because of her enslavement Vitória had travelled the breadth of the Portuguese world. Her testimony allows us to trace her life which consisted of stays in different cities, punctuated by transport over sea, including during her attempted flights to Northern Europe (see map). At the same time, Vitória must have had an intimate relation with the de Milão household, as they had taken the risk of revealing their religion to her and had taken her into the faith. Much trust must have been placed in her, as she was freed and given the responsibility of attempting to bring the household’s daughters out of Portugal.

Vitória “speaks” to us through the documents, yet most of what she could have said is silenced, because the inquisition was only interested in very specific information. The inquisition wanted to prove that there were practising Jews in the de Milão household. Thus, its questions focused on the making of Matzah (unleavened bread) and Vitória’s knowledge of Jewish laws. Vitória meanwhile tried to prove that she “was a very good Christian, and never acted against the faith”. In short, few real details about Vitória’s life are revealed in the more than 60 pages of the statements about her. In both investigations, the inquisitors not only wrote for the illiterate Vitória, they also partially dictated what she said as their questions restricted the topics of the interrogation. Inquisitorial interrogations do record the words of the witnesses. But at the same time, witnesses’ words were constrained by the narrow interests of interrogators.

We, as historians, want to know so much about Vitória’s life before the closing days of 1607, but we are left to imagine its specifics. Vitória remembered little enough. Her interrogators cared even less. At the close of her testimony, Vitória was given as second sentence for re-education. This time, however, she and Isabel Gomes, likely managed to flee the country to join members of their household first in Antwerp, then in Hamburg, and then Amsterdam.

July 2, 2025

Bethany Warner, Junior Researcher, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

The 12th edition of the Digital Humanities Benelux conference took place last week at the Vrije Universiteit (VU) in Amsterdam.

The DH Benelux conference is one of the main venues for disseminating research and exchanging ideas within the community of interdisciplinary Digital Humanities research.

As we explore digital methods to further our research on slavery and resistance to it, members of our project team (Britt van Duijvenvoorde and Pascal Konings) collaborated with colleagues at the Huygens Institute (Rick Mourits, Thunnis van Oort and Kay Pepping), to present their work, Modelling the enslaved as historical persons: Extending the Persons in Context (PiCo) model to fit a 19th century slave society.

This presentation illustrated extensions to the PiCo data model to provide more accurate depictions of the relationships existing in colonial societies and the changing nature of social status. This can include someone’s statement related to ‘freedom’, relationships of ownership and enslavement, but also to look for other identifying traits for enslaved people beyond their relationship to enslavement, such as person names and changing statuses.

More details about the model can be found here.

June 23, 2025

Nicholas Sy, assistant professor at the Department of History, University of the Philippines Diliman and External PhD candidate, Radboud University.

Nicholas C. Sy and Eva Maria Lehner broke off from the group who went from Amsterdam to Bonn and, ironically, went from Bonn to Spain for a Congress on the History of the Family. The event was attended by hundreds of historians from primarily Hispanophone but also Anglophone, Francophone, and Lusophone worlds. Nicholas and Eva presented in a two-part panel “Slave family formation in Latin America, Africa, Asia and Europe” organized by prof. Dr. Jan Kok from Radboud University Nijmegen.

Far from quixotic, these back to back panels in La Mancha presented empirical results from large early modern databases, leading to comparative discussions over matters like levels of illegitimacy, child abandonment, and child mortality among the enslaved in Brazil, the Caribbean, the Spanish peninsula, the South African coast and the rest of the Indian Ocean World. Why, for example, were levels of illegitimacy so much higher in the Iberian peninsula and the Iberian Americas than in Iberian Asia? The dynamic discussion was done in both Spanish and English. The congress’s use of Microsoft PowerPoint’s translated subtitling tool was intermittently unsuccessful (misquoting one presenter as being a specialist in Birds and in the World of Warcraft), but no supplementary charades were necessary as some participants translated for others.

What was wonderful about this conference was that Nicholas, for example, was able to watch a panel in Portuguese about the record linkage of large Brazilian databases, which reminded him a lot about the IISG’s own efforts to create and link the same for the Indian Ocean World. After several days in a row of paella and too much ham, Nicholas and Eva left the surprising cold of Spain to return to the warmth of Western Germany.