Philipp Huber, PhD Researcher, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam //

On 30 December 1607, the Lisbon Inquisition questioned Vitória Dias. It had already questioned many others about her. Vitória was part of the merchant Henrique Dias de Milão’s household. This household consisted of “New Christians”, former Jews converted to Christianity but often suspected of secretly remaining Jews. The inquisition’s suspicions were first raised after members of the household had tried to board a ship bound for Northern Europe. Now, they questioned the members of the household, hoping that they would testify against each other. Their goal was to find people who, even after having publicly converted to Christianity continued to practice Judaism in secret.

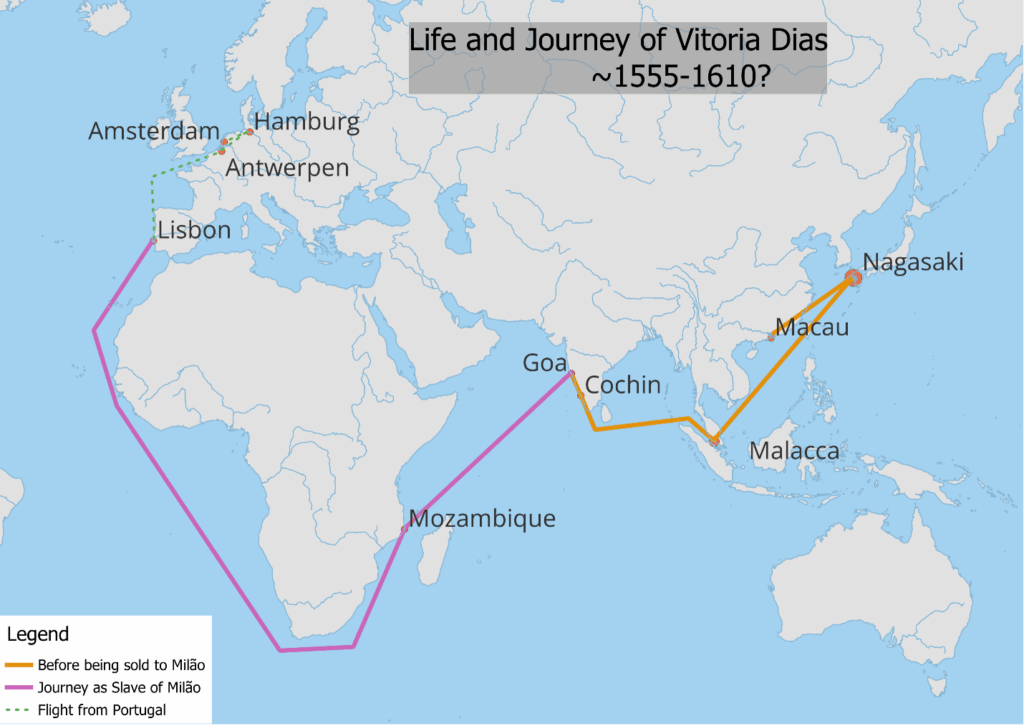

At the beginning of her interrogation, Vitória was asked to provide a brief life history. Her statement reveals that she was different from the other members of this large household in one key respect. While most were relatives of Henrique, Vitória had become part of the household as an enslaved woman, owned by him. Although she had been freed a few years prior, the inquisition still referred to her as a slave. She was not originally from Lisbon, indeed she did not know where she had been born. Vitória estimated her age at above 50, meaning that she was likely born around 1555. She said that she was from China, but did not know in which “realm”(reino) or city she was born. She had been so young at the time of her enslavement, that she did not even remember her parents’ names. Importantly, especially from her interrogators’ religious point of view, Vitória remembered that she had received a Christian baptism on a ship close to Japan. She was later taken to Cochin (Kochi) in India where she was sold to a woman named de Meneses. From Cochin she was taken to Goa, the capital of the Portuguese Empire in Asia, where she was sold to de Milão. She also claimed to have received her Confirmation from the bishop of Goa. When de Milão returned to Lisbon, he took Vitória with him. She had been living with him ever since.

After the inquisitors had written down Vitória’s statement, she was returned to her cell. She stayed there and was questioned thrice more, until on 8 May 1608 she finally confessed to knowing of the presence of Jews in the de Milão household. Later she also revealed that she had been converted to Judaism by Guiomar Gomes, Henrique’s wife, and that she had participated in Jewish rituals together with the others. Vitória was sentenced to re-education as a good Christian in a religious school.

In 1610, Vitória was again in front of the inquisitors She had again tried to flee the country together with Isabel Henriques, the daughter of Guiomar Gomes. For the inquisitors, the most important facts of this interrogation were likely, again, Vitória’s insistence that she had been baptised and, moreover, that she had received Confirmation and knew the most important Catholic prayers (Lord’s Prayer, Ave Maria) as well as the fact that she had received communion while in Lisbon.

To our modern eyes, her travels appear more noteworthy. They reveal that because of her enslavement Vitória had travelled the breadth of the Portuguese world. Her testimony allows us to trace her life which consisted of stays in different cities, punctuated by transport over sea, including during her attempted flights to Northern Europe (see map). At the same time, Vitória must have had an intimate relation with the de Milão household, as they had taken the risk of revealing their religion to her and had taken her into the faith. Much trust must have been placed in her, as she was freed and given the responsibility of attempting to bring the household’s daughters out of Portugal.

Vitória “speaks” to us through the documents, yet most of what she could have said is silenced, because the inquisition was only interested in very specific information. The inquisition wanted to prove that there were practising Jews in the de Milão household. Thus, its questions focused on the making of Matzah (unleavened bread) and Vitória’s knowledge of Jewish laws. Vitória meanwhile tried to prove that she “was a very good Christian, and never acted against the faith”. In short, few real details about Vitória’s life are revealed in the more than 60 pages of the statements about her. In both investigations, the inquisitors not only wrote for the illiterate Vitória, they also partially dictated what she said as their questions restricted the topics of the interrogation. Inquisitorial interrogations do record the words of the witnesses. But at the same time, witnesses’ words were constrained by the narrow interests of interrogators.

We, as historians, want to know so much about Vitória’s life before the closing days of 1607, but we are left to imagine its specifics. Vitória remembered little enough. Her interrogators cared even less. At the close of her testimony, Vitória was given as second sentence for re-education. This time, however, she and Isabel Gomes, likely managed to flee the country to join members of their household first in Antwerp, then in Hamburg, and then Amsterdam.